DEADLINE for submission is 25 JUNE 2019.

Building on the success of the Yogascapes's "Yoga, Movement, and Space" Conference that was held in Kyoto 2-3 November 2018, the intention is to organise another international conference in Kyoto, Japan. However, the theme evolves beyond a singular focus on 'yoga' to explore from a larger perspective the ways in which the implicated subject is embedded in a complex web of competing and often-times contradictory social worlds that might enable strategic syncretism and unlikely alliances to occur (McCartney, forthcoming in Asian Ethnology).

The intention, then, is to work towards identifying complex intersections of coercion, imaginative consumption, capacity building, and sustainable development from within the multitrillion-dollar (usd4.3 trillion) wellness tourism industry; which, of course, also includes the secular-spiritual tourism of yoga, as well. Therefore, there is ample space to discuss a variety of yoga-related themes within a broader discussion of wellness, from both ethnographic and textual-historical perspectives. This is necessary because as Alex Norman and Xinran Lehto respectively explain, meditation retreats and yoga niche tourism are scarcely studied.

Particularly in relation to the ways in which the global consumer of wellness is coerced into attempting to achieve (self-)development and capacity building goals that are fall quite neatly into the schema involved with internalising desire; which is involved in constructing an identity that enables conformity to the normative expressions of a group; and, which are undeniably part of the bodily fascist, neo-liberal, bio-moral regime of power that Khalikova discusses in relation to nationalism and consumerism. These often elide deeper socio-political currents, obligations, and consequences related to, amongst other things, abstract statist, nation-building objectives. Take, for example, the way in which tourism and development are blended into a nationalist aspiration in India. Often, the ‘hard Hindutva’ is essentialised and softened for banal consumption through, as Aramuvadan explains, the transcoding of Romanticism via appeals to identity, community and history; which operate through reconstituted cultural memory, as opposed to documentable influence. Neoliberalism is an indelible partner of the Indian state’s Hindu supremacist agenda. Which, similar to the rhetoric of global yoga, obfuscates the harder end of ideology through romantic appeals to holism and deep ecology.

One strong focus of this conference is to critically examine propositions embedded within various narratives found within and beyond the marketing rhetoric of the global wellness industry that focus on legitimising and promoting ideology infused into notions of development; which obfuscate via utopian analogues the promise of a better tomorrow. A clear case in point is Nitasha Kaul's work on the RISE OF THE POLITICAL RIGHT IN INDIA: HINDUTVA-DEVELOPMENT MIX, MODI MYTH, AND DUALITIES, in which Kaul argues that: The success of contemporary right-wing nationalism has relied upon a systematic projection of the mythology of a new kind of leader who acts in an emotive realm of politics, promises to take people back to “the golden past as future,” [...] The “Modi myth” that projects him as an ascetic, paternal, and decisive ruler. This political myth is constantly reinforced through medium, speech, and performance. This can be compared with Amanda Lucia's ideas around Saving Yogis: Spiritual Nationalism and the Proselytizing Missions of Global Yoga in which Lucia argues, that: North American yogis export yoga globally through proselytization, marketing, and yoga sevā (“selfless service”) tourism. It reveals how these modern yogis construct the practice as a universal good, and the benefits of “doing yoga” are often parsed with religious language. The author argues that the current hypermobility of yoga is more productively analyzed through missiological models of proselytization and conversion as opposed to economic models of production and consumption.

Touching, briefly on sevā tourism, or in the example below, service adventures, it is worth pondering what sort of power dynamic dominates this domain. This is highlighted by Mary Mostafeanezhad, who describes as the 'politics of aesthetics', in which volunteer tourists aestheticise poverty by describing it as authentic and cultural, and in so doing perpetuate an aesthetic structure that depoliticizes poverty. The wellness movement relies, instinctively, it seems, on reward coercion. Still, can we say more about the dynamics of yoga tourism in relation to sevā tourism and its pathological twin, poverty tourism? What exists beyond glossy websites and stories of helping kids in Nairobi or Phnom Penh slums align their hips and engage mūlabandha?

The wellness tourism sector of the global tourism industry continues to grow at a rate faster than any other sector. Wellness tourism has become a legitimate way to travel. And, while this might be good for the individual consumer's self-development, the global carbon supply chain shows that the tourism industry is responsible for around 10 % of the world's carbon emissions. Also, 'over tourism' and 'tourist pollution' have become the defining features of the global wellness/tourism market. Therefore, exploring and identifying through multi-modal analysis the level of misrecognition involved in projecting a sustainable mode of consumption is to be a central characteristic of this conference. Like many countries that rely on tourism, Japan is struggling to create a sustainable environmental and social balance for it's intention to increase tourism. Just like India, which intends to double it's own FTAs (foreign tourist arrivals) from the current 10 million per year to 20 million, within three years, there is no mention of 'sustainable development' in the tourism ministry's documents. Yet, it is the environment that features prominently in the Incredible!ndia 2.0 campaign. As these two examples, demonstrate.

|

|

|

Probably, however, this advertisement that relies on ideas of saving endangered wildlife through tourism is particularly troubling.

But, Do these advertisements sell a lie?

And, while some might bemoan the perceived evils of western, cultural appropriation. These advertisements are made and sponsored by the Indian government. Therefore, how far can the decolonisation of yoga practically go when the neo-orientalist, colonially-constructed myths are reconstituted by the Indian state to sell its own rarefied culture for the sole purpose of profit.

|

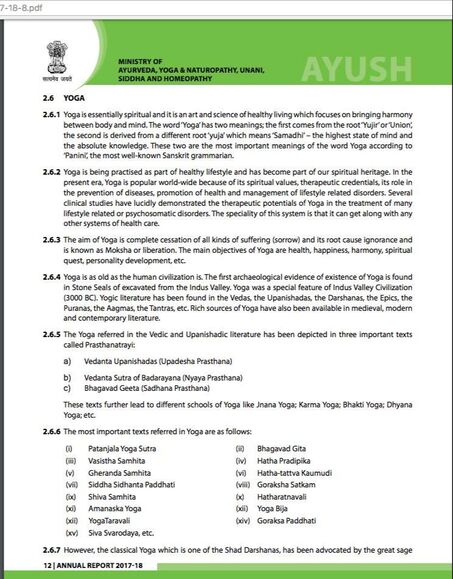

The Indian state and other non-state actors want to promote yoga and oṁ chanting, etc., as a universal cultural product that is open to everyone. The proposition is that it is the bedrock of a universal cultural heritage and not necessarily or specifically, Indian. That yoga is as ancient as time itself. One can see this in the annual report for the AYUSH ministry, which ahistorically links yoga to the Indus Valley Culture through the clay seals, like the Pashupati seal, (see 2.6.4). However, that is another issue of cultural appropriation, since we do not know with certainty what these seals say, yet this factoid is constantly recycled by many to deepen yoga's antiquity. It conveniently avoids the textual evidence that points to haṭha yoga developing from the 11th-century onwards, and not 4000-5000 years ago.

|

Therefore, the politics of representation are to be explored at a textual and ethnographic level to critique the ways in which yoga is instrumentalised for symbolic and economic profit. On top of this, yogapreneurs seem dammed either way. Either they fill up their studios with orientalist images in a way to cultivate that nostalgic mood and romantic ethic, and are then charged with cultural appropriation...or they do the opposite, and do not include any sort of mention of South Asian cultures and religions, which leads to charges of white washing!

Can yoga be inherently Indian and also the bedrock of a universal Urkultur?

Is it fair to promote yoga as a universal construct, but at the same time admonish global consumers of yoga who are enticed by the very reconstituted colonially-constructed, orientalist-inspired marketing that the Indian state uses, as well as culturally appropriated signs from earlier layers of South Asian history; which are not really in any way connected to yoga episteme, at least as far as the knowledge we currently have of it?

Can yoga be inherently Indian and also the bedrock of a universal Urkultur?

Is it fair to promote yoga as a universal construct, but at the same time admonish global consumers of yoga who are enticed by the very reconstituted colonially-constructed, orientalist-inspired marketing that the Indian state uses, as well as culturally appropriated signs from earlier layers of South Asian history; which are not really in any way connected to yoga episteme, at least as far as the knowledge we currently have of it?

Some key words that stand out, include: self-transformation, transformative, self-development, sustainable development, and capacity building. Within the marketing of the global wellness industry there is an interesting rhetorical assemblage of evocative phrases that rely on inspiring growth, not only of the individual, but also the community, nation, and world that relies on a nostalgic-romantic mood, and deep ecological ethic. This leads us to consider the intersection of 'inner wellness tourism', which makes up most of the wellness tourism, particularly to Asia, and what Yvette Reisinger calls 'transformational tourism'. These ideals are clearly seen in the another advertisement from the Indcredible!ndia campaign that focuses on walking in the footsteps of Buddha. And, in the next example, one can see how these inner/transformative tropes are arranged into a wellness retreat.

|

|

|

|

However, there is a flip-side; or rather, a pathological side to this 'journey of the self, through the self, into the self'; which this conference seeks to focus on; which intends to produce outcomes for development into policy. For instance, pilgrimage (using a very secular and broad definition that can include travelling to a meditation/yoga retreat) is meant to in many ways purify the self, through movement. Yet, there are several examples of how pilgrims actually end up polluting the spaces and places they move through in an attempt to purify the self. The pilgrim pollution load can be analysed in many ways. |

The personal, ethical choice to invest in transforming the self through movement and consumption of various levels of wellness packages affects all religions. Take, for example, the pollution caused by the annual Hajj to Mecca; and the pollution caused in sensitive ecosystems in other parts of the world. Here is an interesting example of how wellness tourism and spiritual/secular pilgrimage plus nature combine to promote tourism in the form of a 'spiritual retreat' in Nara Prefecture, Japan. In short, tourism is not good for the environment, yet the marketing of many wellness packages promises a deeper connection to the environment. That does not prevent the legitimation of 'transformative travel' as being perceived as more 'authentic'. As Diane Daniel, explains:

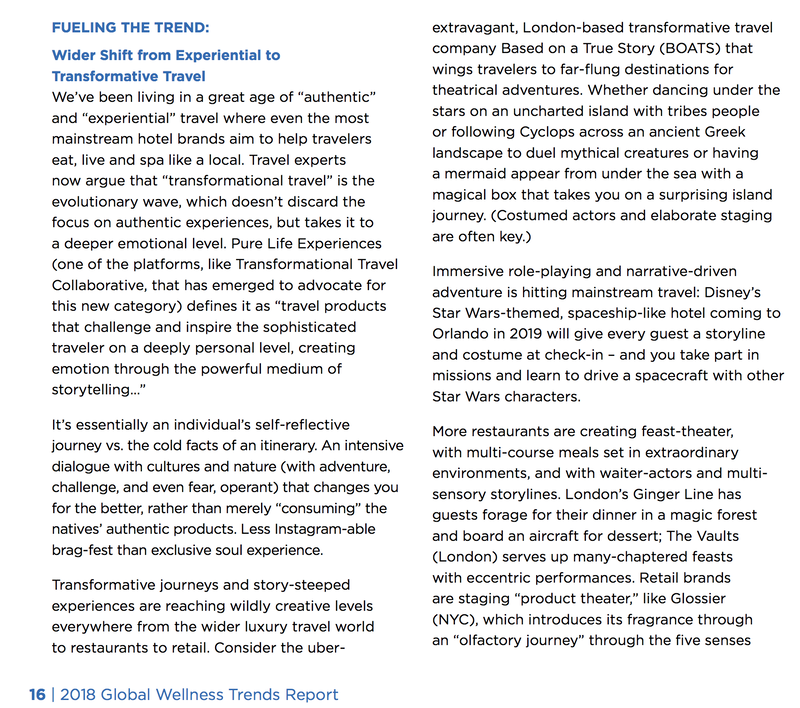

The Global Wellness Summit’s 2018 trend report labeled “transformative wellness travel” a top trend, calling it a step beyond “authentic” or “experiential” travel — one that reaches “a deeper emotional level.”

Below, are some excerpts from the GWS's 2018 report.

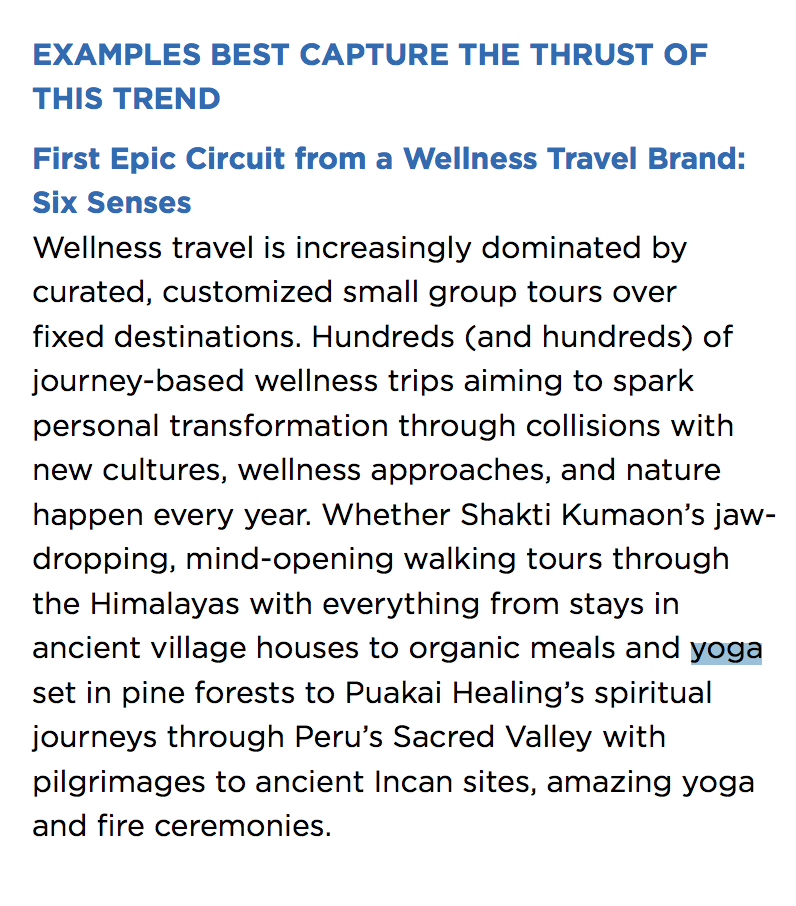

And this is how it is found in the advertising for one wellness retreat company.

And this is how it is found in the advertising for one wellness retreat company.

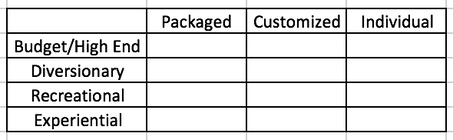

The appearance of sustainability is key, it seems. And, even though tourism can be a key driver in the development, many locations are suffering under the burden of over tourism. The UN declared 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development, how can we understand the potential positive and negative impacts of yoga-inspired wellness tourism? What are the typological features of the yoga tourist? How does yoga fit within the framework of primary and secondary wellness programs? Can yoga-inspired wellness projects achieve social, economic, and environmental sustainability through 'niche tourism' sustainable entrepreneurship? Or, is it a type of rasābhāsa, or, rather, a semblance of sustainability? Therefore, what are the tourism niches that yoga-inspired wellness tourism create? Not only does niche tourism typically appear to be more authentic that mass tourism, it generates a sense of catering to the individual. Building on Arnegger, et. al., Kunz and Ratcliffe explain a potential typology of tourists. Does this work for yoga tourism? Can we improve it?

Recreational tourists are looking for way to regain their physical and mental strength. Diversionary tourists are merely looking for entertainment, in an effort to escape boredom. We can also include Pearce's categories of: packaged, independent and customized tourists.

While the atomized individual is presented with an opportunity to purchase 'authenticity' while also apparently attending to the very real problems of environmental degradation, general social-economic inequalities, political tensions, etc.; the marketing of such wellness yogations, for instance, positions the consumer as somehow helping to alleviate the larger societal burdens related directly to their investment in self-transformation. Yet, the consumption has its own consequences. Also, it is through consumption that the individual is empowered to feel as if they are contributing to a better world through first, helping themselves. Perhaps, as Farah Godrej asserts, there are productive ways for the neoliberal yogin to navigate with agency to counter the coercion of neoliberal governmentality that are ultimately emancipatory? However, these circuits of desire that Margot Weiss describes call our attention to the how late capitalism and neoliberal rationality create circuits of exchange between capital and embodiment. This speaks to the 'performative materialism' that much of the rhetoric from wellness tourism producers use that obfuscates through referencing the numinous, intangible, and non-material benefits of consuming their wellness packages. Furthermore, this reward coercion, particularly in the workplace, is an insidious form of wellness governmentality that urges us to explore it globally from both legal and political-economic perspectives.

If you are interested in participating in this conference or knowing more about it, contact: [email protected].

Alternatively, complete this short form to submit your abstract by clicking the button, below.